GitHub Actions, GitHub's CI/CD solution, are a convenient and widely used way of automating tasks around your repo. Building your code and running tests, deploying artifacts, creating releases, or managing pull requests and issues is all possible there. A great strength of the GitHub Actions ecosystem is also the fact that anyone can create reusable actions that you can use in your workflows.

However, GitHub Actions are not exempt from vulnerabilities. They can pose risks to the repository and its users if attackers can hijack certain workflows. CI/CD environments are attractive targets for attackers, as they can contain deployment tokens, signing keys, or provide write access to a repo. Past incidents, such as tj-actions/changed-files or the Nx "s1ngularity" attack show that attackers have GitHub Actions on their radar, and they are actively exploited to start supply chain attacks.

To support SonarQube's GitHub Actions scanning features, we started to research the ecosystem and stumbled across a pattern we dubbed Zombie Workflows. Attackers could have abused it to exploit vulnerable workflows, even after they seem to have been fixed. GitHub has deployed a change to mitigate the underlying issue, so we can explain the details of how Zombie Workflows work without any risk of in-the-wild exploitation.

A GitHub Actions classic: Pwn Requests

A classic example of GitHub Actions vulnerability are Pwn Requests. These are workflows that run when a pull request is opened or updated, use data from the pull request in an unsafe way, and hold sensitive values. Unsafe usage could mean unsafe interpolation of the PR title, running scripts from the PR, and more. Sensitive values are either repository secrets, such as access tokens or signing keys, or a privileged GitHub access token that provides write access to the repository. Vulnerable workflows typically run on the pull_request_target event.

For public GitHub repositories, Pwn Requests can be opened by any user on the platform by forking the target repo, making a change, and opening a pull request. Let's look at an example:

on: pull_request_target

permissions:

contents: write

jobs:

build:

name: Build and test

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

ref: ${{ github.event.pull_request.head.sha }}

- uses: actions/setup-node@v1

- run: npm install && npm build

- uses: completely/fakeaction@v2

with:

arg1: ${{ secrets.supersecret }}When a pull request is opened, the workflow clones and checks out the PR changes. It then runs npm install and npm build in the directory of the PR checkout. This will lead to arbitrary code execution, as an attacker can simply add a custom build script in the package.json file. Executing code in the workflow environment gives the attacker access to all data in the environment, such as the secret used in the last step of the workflow, or the privileged GITHUB_TOKEN.

Let's fix the vulnerability to protect our CI/CD pipeline. First, we should switch from pull_request_target to the pull_request trigger. This will prevent external PRs (those from users who have no special permissions in the repo) from getting any write permissions or secrets, even if they are explicitly stated in the workflow file.

Second, we could switch the permissions to read, and move the last step into its own workflow since it can't have access to secrets anymore due to the use of pull_request. Attackers can still execute arbitrary code during a workflow run, but because we removed all sensitive secrets and permissions, there is no impact anymore. We push our workflow vulnerability fix to the main branch and are done. Crisis averted!

But wait, what's that?! We still got exploited after we pushed the fix? We can see that there is a malicious Pwn Request that somehow still exploited our vulnerable workflow. The vulnerability we thought was dead came back to life and haunts us!

Zombie Workflows

We dubbed this vulnerable pattern Zombie Workflows because they appear to be coming back from the dead. Let's dive in to see what happened.

When a pull request triggers a workflow, there are multiple things that need to be resolved by the GitHub Actions runner. What's the Git history's head? Which version of the workflow should I run? Which files do I need to clone?

To prevent attackers from simply modifying the workflow file in their PR changes and then letting GitHub execute it for them, there are some safe-by-default settings in place. The Git history head is the latest state of the base branch. This is the branch in the target repo that the PR wants to merge into. The workflow file is also taken from this branch, since this file can be trusted because it is already part of the repo. By default, a clone action inside a workflow will also checkout the latest state of that base branch.

However, when a workflow needs to perform tasks on the changes from the PR, users override these defaults. Taking our example from above, we can see that the checkout action will clone the repo and then check out the head branch, which is the external branch with the changes of the PR. Importantly, the workflow file itself is still taken from the base branch. So we should be safe, right?

The problem: When opening a PR, an attacker can decide which branch to target. Since GitHub will always run the workflow version from the base branch, an attacker can decide which version of the workflow to run, including vulnerable ones from forgotten branches.

Scenario 1: Old, forgotten branches

When we fixed the workflow vulnerability, we only pushed the fix to main, our default branch. However, our repo uses branches for things like releases, hotfixes, feature development, etc. At every point in time, there are multiple branches, created from different points in the Git history. Some of the branches might even be very old and unused for years.

When fixing a PR workflow vulnerability, we need to make sure that we apply the fix in every branch. If we don't do it, attackers can look through our branches and our Git history to find fixes that were not ported and exploit them. The only exception to this is when the PR trigger has a branch filter that prevents the workflow from running on unwanted branches.

One real-world example of such an attack might be the Nx "s1ngularity" attack. In their post-mortem, the Nx maintainers mention that a vulnerable workflow was likely exploited after they had fixed it. While they don't mention the exact reason, which might not be reconstructable due to the attacker covering their tracks, but the overall behaviour does fit the Zombie Workflows pattern.

Scenario 2: New, unmerged branches

Instead of exploiting old, forgotten branches, attackers could also watch a repo and wait for a vulnerable workflow to be committed to an unreviewed feature branch. Even if the repo maintainers have a strong review process that would catch vulnerabilities before they're merged into the default branch, these changes have to exist in some branch in order to be reviewed.

Since attackers can open a PR on any base branch, there's nothing preventing them from triggering a new workflow before it has even been reviewed. We are not aware of any real-world cases of this scenario, but there could have been undetected cases. However, this attack scenario usually has a smaller window of exploitability

Findings

When we realized that Zombie Workflows are a thing and that very few people know about and consider this GitHub Actions behaviour, we started a large-scale evaluation of popular repositories to find out how prevalent Zombie Workflows are.

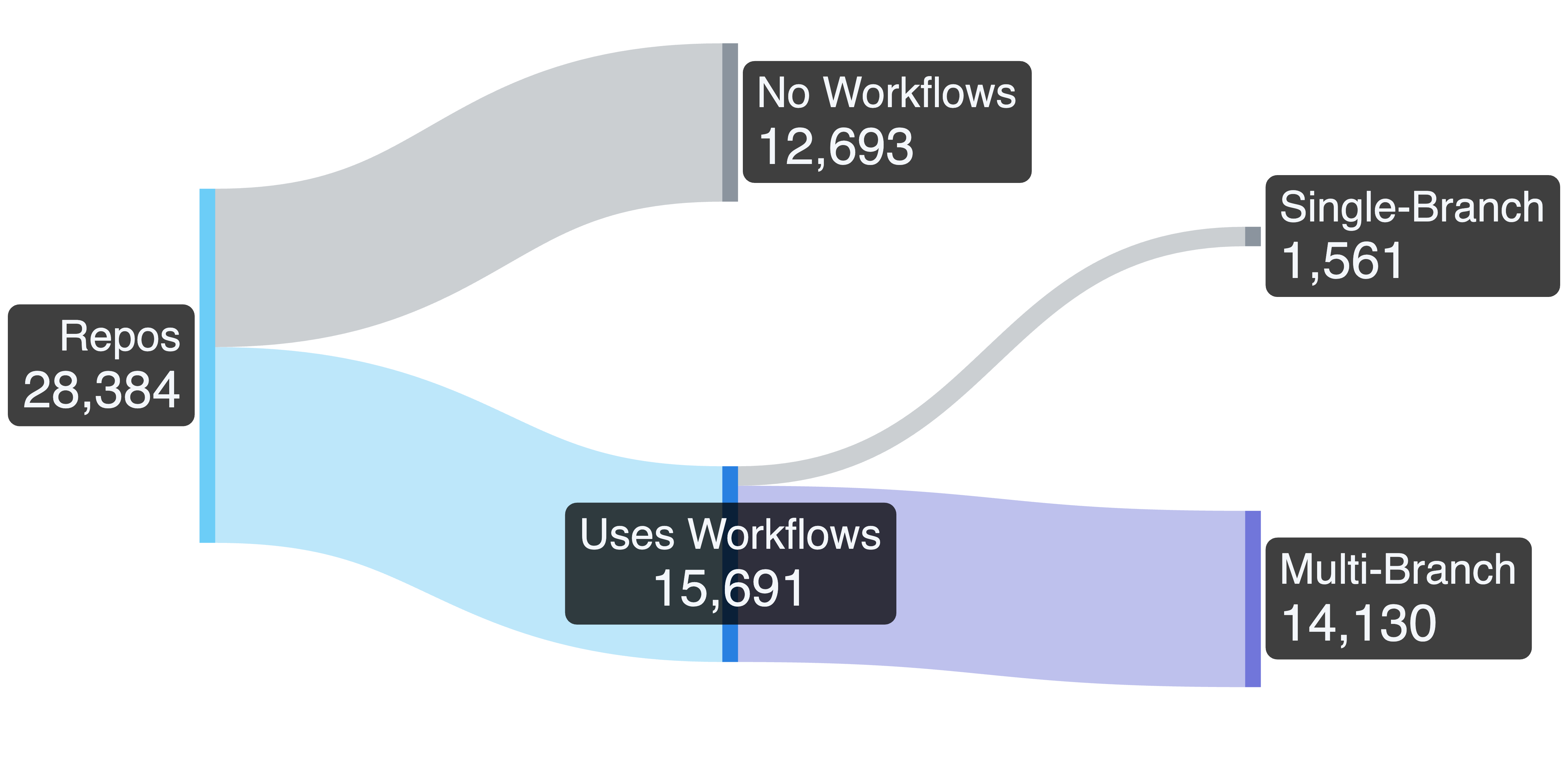

We started by crawling the workflows of top repositories with more than 2000 GitHub stars. This limit was arbitrarily as a rough proxy for the popularity of the repos. This left us with 28,384 repositories from which we filtered out repos not containing any workflows, leaving us with 15,691 repos that do use GitHub Actions. From these, we removed all repos that only have a single branch, because by definition, there couldn't be Zombie Workflows here. This left us with 14,130 repos that we needed to scan for workflow files:

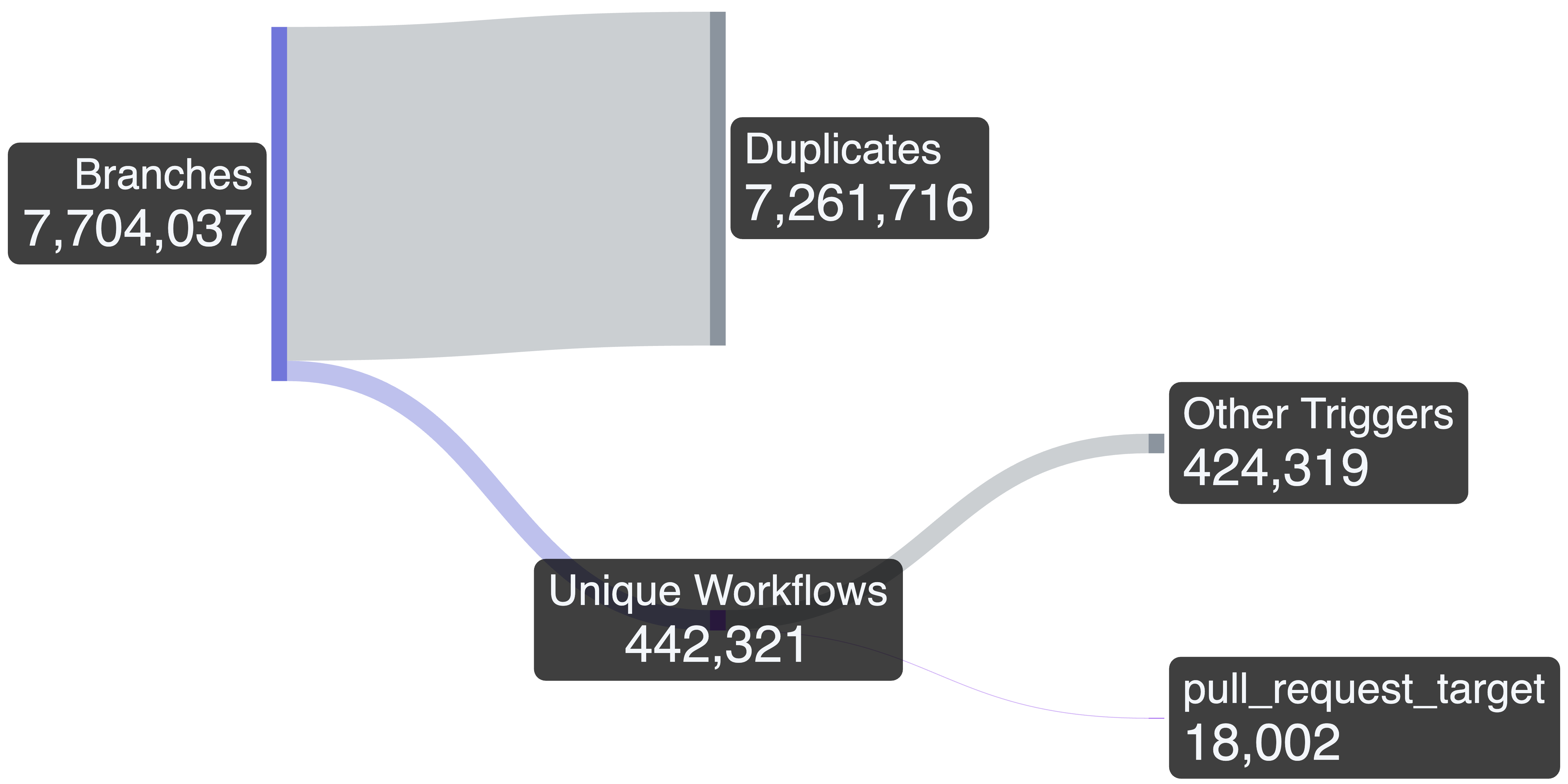

After searching through all 7,704,037 branches of these repos, we found 442,321 unique workflow files. Many of these unique files are different versions of the same workflow, found in different branches that capture the workflow file version at the point in time when the branch was created. Since the only trigger for a Zombie Workflow is pull_request_target, we filtered out all workflows that didn't use this event. This gave us 18,002 workflows that are potentially attackable by a Pwn Request:

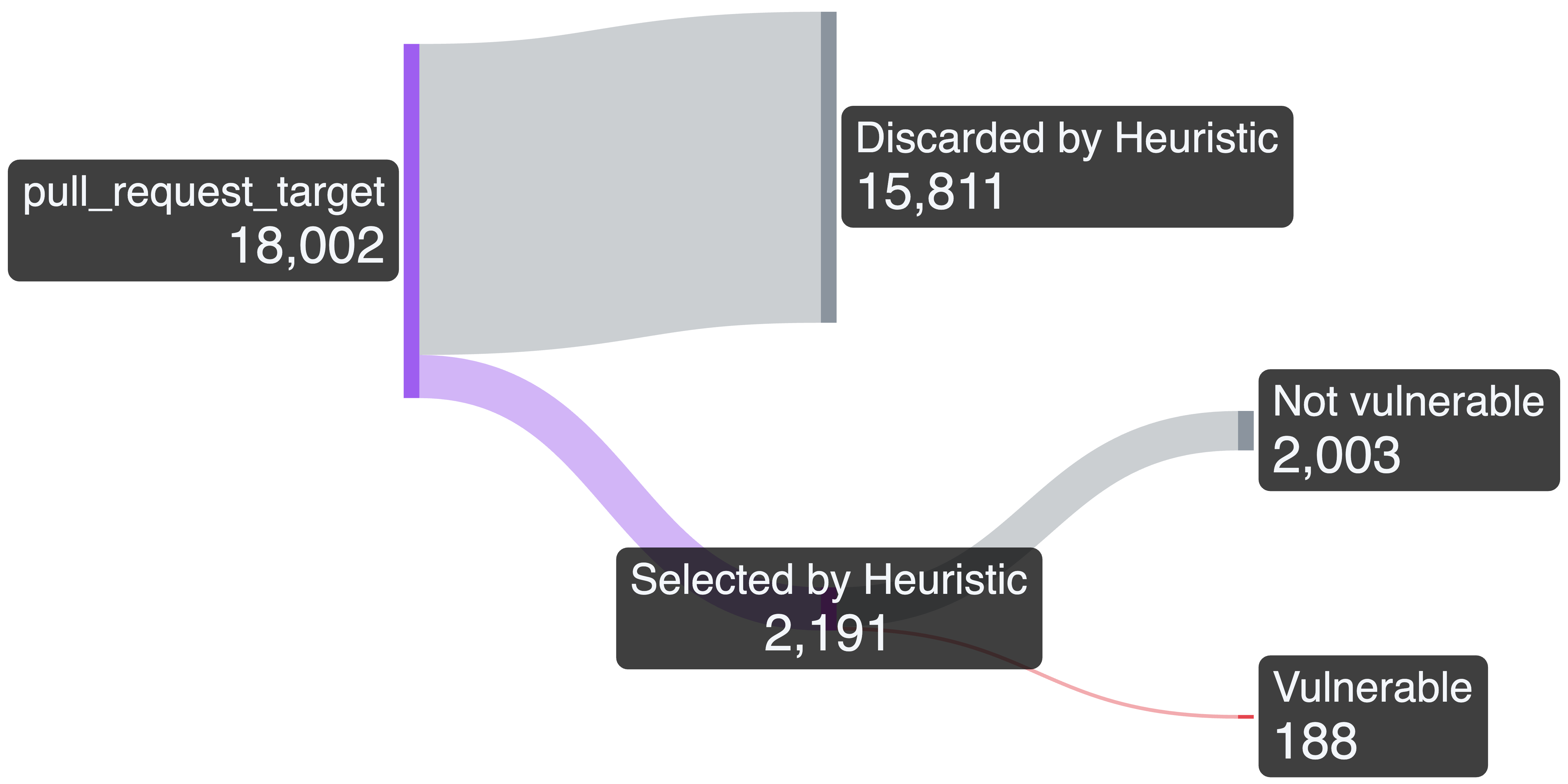

Since this number was still too large to triage manually, we created a heuristic that only kept workflows that check out the head branch and have a potential impact. To determine this, we checked if the workflow used secrets other than GITHUB_TOKEN, or if the permissions were either explicit write permissions, or implicit write permissions derived from the defaults. This resulted in 2,191 candidate workflows out of which we identified 188 to be vulnerable:

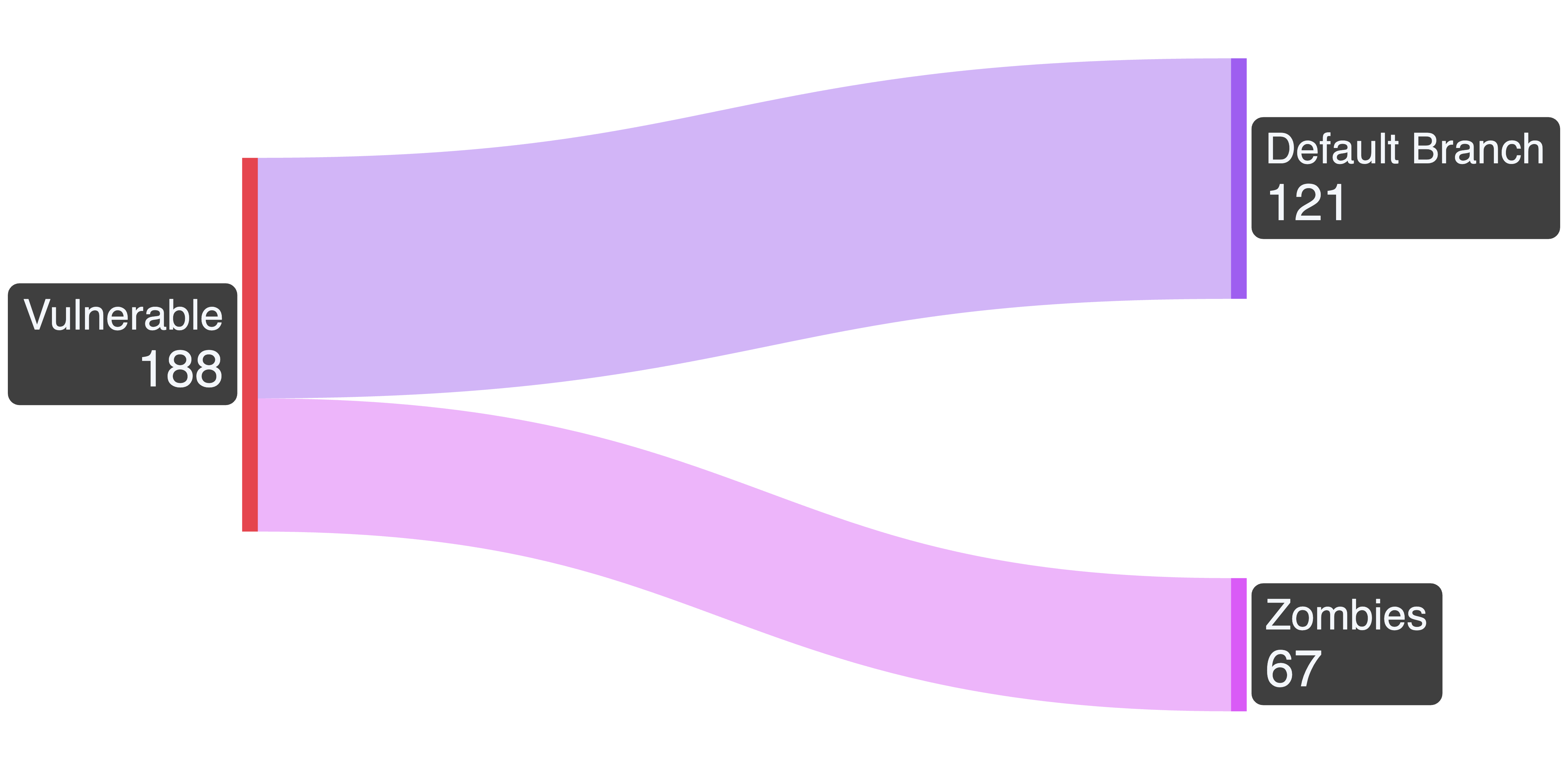

As a final check, we verified if each of the vulnerable repositories is indeed only vulnerable in non-default branches, or if the vulnerability still exists in the default branch. To our surprise, a majority of 121 workflows fell into the latter category, making us end up with only 67 "true" Zombie Workflows:

The 188 vulnerable workflows are just a lower boundary, as our heuristic could have excluded many exploitable ones that follow a different pattern than the one we searched for. During our manual triage, we stopped when we found one vulnerable version of a workflow in each repo, so the absolute number of exploitable branches is higher.

Among the confirmed vulnerable repos were projects with tens of thousands of GitHub stars in organizations such as Microsoft, llama.cpp, Cypress, LLVM, NVIDIA, Apache Foundation, and Azure.

Disclosure and patches

Once we were done with our evaluation, we started the long process of disclosing these vulnerabilities to the respective maintainers. In the best case, this includes manageable, but still non-negligible amount of work: Verifying that it is indeed exploitable to avoid sending out false-positive reports, creating a comprehensive report, submitting it to the maintainers, and helping with follow-up questions.

In a lot of cases, there was even more work involved before we could even send the report: tracking down active maintainers and their preferred ways of vulnerability reporting, following up via other channels when getting no response, etc. We knew this from our past years of reporting vulnerabilities to open-source projects, but with 188 vulnerabilities, this was on a different scale.

This is why we were very relieved to see an announcement from GitHub on November 7. They announced to change the default behaviour of pull_request_target-triggered workflows. Starting from December 8, such workflows will use the workflow version from the default branch instead of the base branch.

This effectively fixes the Zombie Workflows pattern because vulnerability fixes don't have to be backported to all branches, and new branches cannot be exploited before they're merged into the default branch. While we are still continuing to report the issues in default branches, this platform change was very effective in securing a lot of projects at once.

Summary

GitHub Actions are widely used but are also interesting targets for attackers because they're not exempt from vulnerabilities and can hold sensitive tokens and privileges. While the concept of Pwn Requests has been known for a while, there was a pattern attackers could use to exploit seemingly fixed workflows, which we call Zombie Workflows.

We want to express kudos to the GitHub team for doing the right thing by introducing a breaking change that increases the security of the whole platform at once, preventing Zombie Workflows. However, there are still other types of GitHub Actions vulnerabilities that your workflows could be vulnerable to. To ensure you can trust your code, scan your workflows with SonarQube to detect real-world issues like the ones explained in our recent blog post.

Related blog posts

- Securing GitHub Actions With SonarQube: Real-World Examples

- Ollama Remote Code Execution: Securing the Code That Runs LLMs

- Caught in the FortiNet: How Attackers Can Exploit FortiClient to Compromise Organizations

- Code Security for Conversational AI: Uncovering a Zip Slip in EDDI

- Double Dash, Double Trouble: A Subtle SQL Injection Flaw